Als letzter Beitrag in der Reihe über Henry Craik folgt hier noch ein Nachruf, der heute vor 150 Jahren in der Zeitung The Bristol Mercury erschien.1 Im Vergleich zu den eher allgemein gehaltenen Lobeshymnen in der Western Daily Press entwirft er ein wesentlich lebendigeres und differenzierteres Bild Craiks (einschließlich einiger Schwächen). Der Verfasser war Richard Morris (1813–1894), Baptistenpastor an Craiks Wohnort Clifton.

IN MEMORIAM.

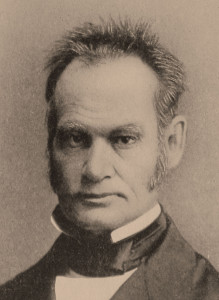

THE REV. HENRY CRAIK.

By the Rev. R. Morris, Clifton.Scotland has seldom given to the south a richer gift than that received in the life and character of Henry Craik. Scotch adventurers may be found everywhere, while her sons of toil, genius, and culture adorn every land; but in the career of our deceased fellow-citizen we have lost one whose adventurous spirit was controlled by a deep-toned piety, and whose ripe scholarship and unadorned eloquence of life and tongue made his presence amongst us of incalculable worth. Happily, in his case, he was a man of appreciated goodness and felt power. He was the last to desire a complimentary epitaph when gone, but the first to wish to hold a place after death in the memory and affection of the good and faithful.

We sincerely trust the memoir to be published of this esteemed servant of Christ will give to the public a definite and living portrait of his character. The events of his life were simple; they were neither startling nor unusual. By the side of his esteemed colleague, the Rev. Mr. Müller, it appears tame and unimpressive. The Orphan House and its christian missions have so striking an effect from their diffusive beneficence, and the thrilling report of their dependence and yet increasing progress, that the quiet ministrations of Henry Craik have almost escaped the attention of the public. But his life and character were full of incident and meaning. His character was unique, his life singular. They may be made productive of great good. Though dead, he yet speaks. We sincerely trust that the voice coming even from the grave will be listened to by many an obedient ear and loving heart.

We would respectfully urge the estimable man to whom his papers have been entrusted,2 rather to delay the memoir, than fail in infusing into the detail the genial spirit of our departed friend.

His appearance was at times almost grotesque, and but for a watchful home, we suspect it would have been as alien from the ordinary secular, as from the clerical garb. We have sometimes been with him when the broken umbrella, his faithful friend, and the oldest hat have, by mistake, been donned for the best attire. The collar of the coat was looking after the sleeves, and the necktie had comfortably nestled itself behind the head. When in such a state he had just come to the surface after a deep digging for a Hebrew root, or a dive into the depths of authorities to see whether the Keri of the Hebrew should be admitted into the text. His intense devotion to the study of the Scriptures made criticism a recreation, and in his most humorous, impassioned, or depressed moments it was never unwelcome. When amidst beautiful scenery, and affected almost to tears by its witchery, a passage of the Divine word would come to crown the scene. But with it would occur the readings and interpretations that reverence or enmity had ever suggested. Nor did this break the spell. If a critical friend was present, nature would have to wait, till the moot point was settled. Then the landscape came afresh, the more fascinating and beautiful that it had not rebuked his momentary forgetfulness of its charms. Poetry and sentiment at times lured, but never mastered him. He could enjoy the one and indulge the other. But they were recreations enjoyed, but not obeyed.

His unsuspicious nature and purity of character were without weakness, but not without peril. They exposed him to deception. When doubt of truthfulness was awakened, his watchfulness and resoluteness proved that his simplicity was only guilelessness, and his trustfulness the triumph of charity. He was ever ready to confide, slow to detect, but when deceived indignant in rebuke. Intentional deception he could not endure. To be acquainted with him was to respect him, and to know him was to love him. His trustful conversation, kindly fellowship, Scotch reminiscences, love of fatherland, English sympathies, devout spirit, made him, to the few, more of a model friend than he had been accepted by the many as a model preacher.

An oppressive sense of responsibility checked indulgence in mere literary pursuits, yet he found time to keep abreast of the current literature of the day, and watch with deep solicitude the phases of the controversies that were disturbing the Church of Christ. In some he took an active part, in nearly all a deep interest, and if he had lived, this winter would have witnessed his indignant condemnation of the modern attempt to create a church, or reveal a religion, without a creed. He had purposed a series of lectures to remonstrate against this attempt. While holding with an eager grasp the old standards of the evangelical faith, he grew in catholicity of spirit. His reading had become more liberal, his public services less confined, and his friendships more extended.

In his early life he had passed from the home culture and discipline of an estimable Scotch clergyman to a tutorship in the South of England.3 The education of home and of the University of St. Andrews had prepared him to do honour to his new position. He was highly esteemed, and still true to his early devotion to classical studies. An apparantly [sic] accidental association with Mr. Müller, gave young Henry Craik fitting opportunity for the revelation of his power. He became an earnest acceptable preacher of the Gospel. Adopting the views of the Baptists, his course was in the main prescribed. He did not join the Baptist denomination, but, with Mr. Müller, came to Bristol, and sought to establish a Christian Church. An open and unpaid ministry was the principle on which the attempt rested. They met with many suspicions and much opposition from the religious public. Both these honoured men, with instinctive wisdom, gave themselves mainly to work. The one to become the prince of our philanthropists, the other the model student and preacher. In each department success came.

Religious controversy was to them an unwelcome employment. Teaching, preaching, and working, their loved service. The small company soon became a formidable following. Generous and liberal helpers unexpectedly sprang up, and from the East the tribe travelled West, until Salem and Bethesda chapels became the accepted substitute for the name of a sect, and Ashley-down Orphan Asylum the evidence of a noble beneficent triumph. Faith in the Word was honoured in the chapels. Faith in the Work was blessed in the Asylum.

Of Mr. Müller we need not write. His monument time has already reared. Those structures of real magnificence, that form the home for nearly 2000 orphans, both conceal and reveal the nobility and simplicity of his character. His deceased friend claimed no such honour. His devotion was emphatically to the Divine Word. He laboured and watched to catch its very whispers, while his hearers received from his lips the fulness of its counsels, and the wealth of its revelations. Biblical words were to him as caskets. He suspected a jewel in each. He erred sometimes, but not often. The grammatical value, rather than the spiritual force of a passage, would captivate him. The form became more important than the principle it embodied. But these instances were few in contrast with the abounding of fruitful and sober exegesis. We would pass them by, if veneration for his memory did not demand an exact likeness of our friend. With these admissions, we leave Mr. Craik, confessedly, one of the very best commentators that Holy Scriptures ever had. Through him for thirty years their infinite variety and resource have ministered to the guidance and consolation of thousands of hearers.

We would confess our deep regret that he has left behind him commentaries on only one or two portions of the Scriptures. His independent criticisms on Alford, Bishop Ellicott, Tregelles, and Scrivener have been gracefully appreciated by these learned men, and they probably would share the regret that so successful a student and critic had not lived to record his matured judgment in a written commentary on the text. His work, however, is done, and the absence of the teacher should make the student the more solicitous, habitually to be taught of God.

As if impelled by some pre-monition of his approaching removal to his better home, he had long indulged the hope of visiting the scenes of his early days. The opportunity came, and he joined his honoured brother’s family, sojourning amidst the lake scenery of his native Scotland. To him, more than to many, such companionship, scenery, and associations would yield intense joy. A joy the purer, in that so much of Heaven would be blended with the scenes. But disease brought disappointment, and soon he was compelled almost to hasten back to his home at Clifton. From this there was one continuous descent to the grave. A long and painful illness ensued. Loving hearts and medical skill and care joined to stay the hour of departure. He himself had the impression that his work was not yet done. To his honoured brother, with another friend present in this chamber of sanctified affliction, he expressed the wish that he might yet bear the fruits of bygone labours into the earthly storehouse of his great Master. His desire seemed natural. Such stores as he possessed could not, in human seeming, be spared. They were more needful for earth than heaven. But not so was the decree of infinite wisdom and love. By such discipline are we taught that though God puts such treasure in earthen vessels, the vessels are not the treasure. They may be broken, but the riches remain.

The last days of our departed friend were those of suffering and exhaustion. Amidst all, peace reigned. His soul stayed itself on God. There was no exultation, but much tranquillity. Neither doubts nor distrust disturbed his last moments. All was peace. Once he said, as we were standing by his bed-side, “God’s presence is precious; I feel its value; it is my stay, my hope; but it is good to have about me and in my chamber those I love. I feel how merciful and kind it is of my heavenly Father to give us these objects of human affection and sympathy. I like their presence; they help and cheer me.” His beloved wife4 and dear daughter5 were moving about his tender heart, and soothing its sorrows, and assuaging its pains. They were ministering to his peace. And thus in them his keen eye of faith and love saw his Lord. They to him were gracious and needed gifts from His hand. The last words addressed to us when passing round his bed of langour and pain were, “Dear M—, when you hear it is all over, give God thanks.” These words followed us. They enjoined a duty we knew to be well nigh impossible to obey. It would require great resignation and faith to praise God for taking away such a man and such a life as Henry Craik’s. But we have learned already that often an apparent loss is a great gain. To him this must be, and to us it may be true. We may, then, calmly say, “The Lord gave, and the Lord hath taken away; blessed be the name of the Lord.” It is all over; let us give God thanks.

He was carried to the grave on Tuesday, amidst the sorrows and regrets of thousands. Whether by design we know not, but with marked propriety the Cathedral bell was tolling as the funeral passed through College-green; and in Bath-street the shops and offices of the Jewish merchants and traders were partially closed. The day was gloomy; the very heavens seemed to sympathise with the sorrowing crowd. A long line of carriages and mourners followed the remains to the cemetery, and there thousands were waiting the interment. Among them were nearly all the Baptist and Independent ministers in the city. A clergyman, Mr. Doudney, was present. Two brethren officiated, and gave utterance to the sympathy and sorrow that prevailed. All was genuine. Each seemed to be bearing a heavy burthen. It was felt to be a time to mourn and weep. A master in Israel had fallen. But the sorrow was not as those without hope, for all felt, “Blessed are the dead that die in the Lord.”

Bristol has lost many citizens and benefactors during these last twenty years; the broken columns and massive monuments of our cemetery tell of losses that no language can express. But of all, none surpass that which has been sustained by the church and the world in the death of Henry Craik. Neither mural tablet nor marble monument is needed to perpetuate his name. A multitude now and many hereafter will trace their likeness to Christ to his ministration. It will be increasingly seen how largely the Divine Spirit used him to awaken to life and mould into spiritual beauty the new creature in Christ Jesus. And in the impress of the Lord stamped on the new character, shall be traced the faithful work of the under-servant who laboured for such a joy and such a reward. “They that turn many to righteousness shall shine as the stars for ever and ever.”

Let us breathe the prayer that we may follow in his steps, so that “to live may be Christ, to die gain.”

Redland, February 5, 1866.

Anmerkungen:

- The Bristol Mercury, 10. Februar 1866, S. 6. Eine erweiterte Fassung wurde im März 1866 im Baptist Magazine sowie als separate Broschüre veröffentlicht.

- Gemeint ist William Elfe Tayler (1812–1869), der Herausgeber der Passages from the Diary and Letters of Henry Craik.

- Craik arbeitete 1826–28 als Hauslehrer in der Familie von Anthony Norris Groves in Exeter und 1828–31 in derselben Position bei John Synge in Teignmouth.

- Sarah Craik geb. Howland (1812–1892).

- Entweder Sarah Ellen Craik (1844–?) oder Julia Craik (1847–1884).