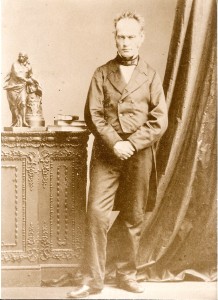

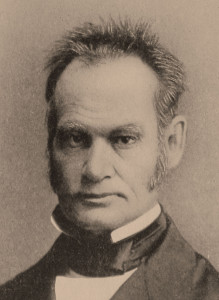

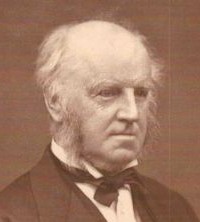

FUNERAL OF REV. HENRY CRAIK.

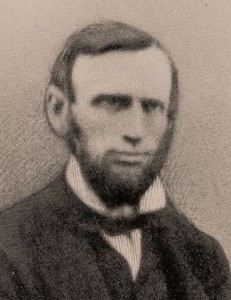

A stranger visiting Bristol yesterday could not fail to observe that a funeral ceremony of unusual importance engaged the attention of the citizens. The leading streets and thoroughfares were occupied by groups waiting to see or to join the procession which carried, in sad solemnity, the body of a beloved minister to the grave. The route was a long one of four miles, extending from Hampton Park to Arno’s Vale. The funeral left Mr Craik’s residence about 10.30, but it was after twelve when the long line of carriages – the longest ever seen upon a like occasion – reached the cemetery, where hundreds had been waiting for hours in the rain and cold of a gloomy, wintry morning. The weather must, of course, have deterred many from going out, but at every part of the route the funeral was met by sympathising spectators. In Queen’s Road, at the Triangle, a body of ministers and friends joined it. At Counterslip we observed a large number of the workmen of the great sugar-house – many of them had been accustomed to Mr Craik’s ministrations in the room provided for the purpose at the works, and they evidently felt the loss which they had sustained. At the railway station and other parts, cabs and carriages filled with ladies in mourning testified to the feeling in which Mr Craik’s memory was held. As might be supposed, the other name associated with Mr Craik’s for the long series of 34 years – the name of George Muller – was frequently in the minds of the mourners, and many expected to see him yesterday. He could not attend, owing to severe indisposition, which has kept him for two or three Sundays away from his usual public duties. We may be sure, however, that no one more sincerely mourned the loss of “Brother Craik,” as he always styled him, than the great founder and director of the Ashley Down Orphan Houses.

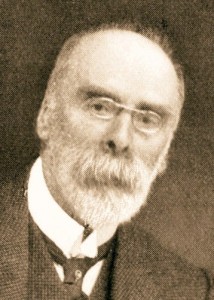

At the cemetery it was found impossible to admit even a small proportion of the immense crowd seeking admission to the chapel – a crowd which extended beyond the portico and spread itself over the cemetery, waiting patiently for a glimpse of the coffin as it was carried to the grave. Major Tireman, a prominent and able preacher among “the Brethren,” was chosen to officiate in the chapel, and the Rev. Mr Victor, of Clevedon, at the grave.

The chief mourners were the three sons of the deceased, Mr Conrad Finzel, Major Tireman, Messrs Howland, Acland, Rickards, C. Lemon, and the Rev. Mr Victor. Eight deacons of the Bethesda Chapel were present, viz., Messrs Martin, Butler, Feltham, Pocock, Withey, Jos. Matthews, Isaac, and Captain Beecher. In the other coaches were the Revs. Aitchison, Robinson, and Larkins, and Messrs Horne, Davis, Wright, B. Perry, Jno. Thomas (Clevedon), B. Thomas, Elliot Armstrong, Wm. Stancombe, Hatchard, Shoobridge, Chapman (Barnstaple), Hake (Bideford), Lawford, and Hallett. In a carriage in the procession were Mrs Muller and her two sisters, and nearly 30 private carriages followed in the rear. Amongst those who had joined in the procession to show their respect for the deceased, were the Revs. N. Haycroft, M. Dickie, R. E. May, H. I. Roper, E. Probert, R. P. Macmaster, J. Tayler, T. A. Wheeler, Dr. Gotch, D. A. Doudney, E. J. Hartland, U. Thomas, and Messrs H. O. Wills, F. Wills, Griffiths, Grundy, Gould, Mack, Poole, G. W. Isaac, Batchelor, &c. When the coffin had been deposited in the chapel, Major Tireman, having read the latter portion of the 15th chapter of 1st Corinthians, and offered up prayer, founded an address upon the 13th verse of the 14th chapter of Revelations: “And I heard a voice from heaven saying unto me, write – Blessed are the dead who die in the Lord from henceforth: yea, saith the Spirit, that they may rest from their labours; and their works do follow them.” He remarked that when the beloved disciple John heard that voice from heaven under circumstances of humiliation and depression, the companions of tribulation, he was led to see far greater revelations of the coming kingdom and glory of the Lord whom he loved than he had ever experienced before. So they might believe that the cloud of great and deep sorrow under which they were labouring would be made subservient to a deeper spiritual experience and a deeper spiritual joy. It was not said blessed are the dead. There was nothing blessed in death – it was the struggle with the last enemy that had to be destroyed – it was a penalty to be paid even by every redeemed son of Adam because of sin. The reason of the blessedness was that they “died in the Lord.” Of whom could they with greater truth say this than of their beloved brother? They had, indeed, the comfort and satisfaction of knowing that he died in the Lord. They had a comfortable assurance that he lived in Him, and that was to them an assurance that he died in Him and inherited His blessings. If it could be said of anyone that he lived in the Lord it could surely be said of him whose remains, surrounded by the accompaniments of sorrow and death, were present in their midst: eminently he lived in the Lord, and to him to die was gain. This was the testimony of thousands, and it was not only written in the hearts of those present, but it was a living epistle known and read of all men. Little did he (Major Tireman) think when last in that place, to witness the consignment to the silent tomb of their brother, Mr Hale, who was suddenly taken in the midst of his labours, and when he heard their dear brother address them, that he himself would be the next to go; and much less that he should occupy that place and speak a few words over his remains. But God’s ways were inscrutable, and he (Mr Muller) who was his colleague so long – who was his friend and companion so many years – was himself unable by sickness to perform those last duties. Might God long spare him, and not add sorrow to their sorrow. Pleasant and lovely were they in their lives, and in death they were not divided. He was laid aside in God’s providence, and this alone prevented him from paying a last testimony to their brother. He (the speaker) was there because Mr Muller, and the family of the deceased, would have it to be so – not as one worthy to address them – but as one who yielded to none in respect for the character and integrity of life of him with whom he had been united for 15 years in the closest ties of friendship. The delight of our eyes was gone. Of him it might be truly said – Si monumentum quæris, circumspice – “If you seek his monument, look around” – in the sorrowing hearts and tearful eyes of the thousands of sorrowing sons and daughters of the Lord. Surely when he fell a pillar was broken in the house of our God. They had lost one who for 40 years devoted his life to the services of his God and Master. All his vast energies, and qualifications, and endowments were employed for one purpose – that of making more and more clear the Word of God. He lived for one purpose, and died for one purpose. The great delight and consolation of his soul was to make clear the Word of God, and he rejoiced in displaying its untold beauties to others. He left, like Peter, no legacy to the church, but he leaves his name, his works, his character, his example, as a lasting heritage. He combined fervent piety and zeal with childlike simplicity. His very sensitiveness and acute sensibilities may have been a hindrance to the work he was engaged in carrying on. He could not go from house to house without deep feeling on the occasions of sorrow to which he was called to minister. If his character was aspersed he was never moved to any unchristian feeling, much less to any unchristian act. “He was a good man and full of the Holy Ghost, and through him much people were added to the Lord.” His loss had made sincere mourners of them all. They would not be able to feel it as they desired just then; but they would feel it in days and years to come, and feel it deeply. They rejoiced, however, in his blessedness, and in the rest he had from his labours. He had gone to realise the full enjoyment of those truths in which he believed here, and on his dying bed his eyes lighted up with fire at the prospect of being in the fellowship of the blessed. Could they look upon his last remains and their sorrows not be moved? This was the last they should ever see of their much-beloved brother, whose presence they had so often welcomed and which had struck joy into so many hearts. Never again would those lips speak the words which flowed from him like rivers of living water. Never again would those eyes light up with fire and that tongue become the pen of a ready writer, and those hands be lifted up, as they were when he spoke of things concerning the King. Never again would his footsteps fall on the threshold of that place wherein they all so loved to hear them fall, and where he so often gave good counsel and advice. Should their sorrows not be moved? Never again would they hear his little cough with which he entered the room, and which gave an indication of his presence amongst them. Could they think of such things and not sorrow? Major Tireman, having given a few words of earnest and affectionate exhortation to the bereaved widow and family of the deceased, concluded with prayer his deeply-affecting discourse, which was imperfectly heard in the crowd and pressure.

The coffin was then removed to the grave, and, having been lowered in the earth, the Rev. Mr Victor, of Clevedon, addressed the assembly in an earnest and Christian manner. He said the grave over which they met was hallowed, because the sting of death was taken away from him who now was lying within it. The grave was hallowed because of the resurrection of the Lord Jesus Christ, who had made it impossible for this tomb to retain their brother now committed to it. “I am,” said the blessed Saviour, “He that liveth, and was dead, and behold, I am alive for evermore, and have the keys of death and Hades.” “I am the resurrection and the life, he that believeth in Me shall never die.” On this dreary, wintry day, whilst this body was committed to the tomb, the spirit that in-dwelt in it was soaring on high – a lovely bird of Paradise, hymning hallelujahs in the bosom of their blessed Lord. These were hallowed remains in this hallowed grave, because the body was redeemed as well as the soul by the precious blood of Christ – the body was once in-dwelt by the Holy Ghost, through whose power its senses were engaged and employed for their Master in the skies. The eyes saw for Christ, the lips spake for Christ, the hands were lifted in the service of Christ, and in intercession for many. Hallowed memories gathered around this grave. The memory of the just is blessed. There was the remembrance of their brother as a devoted husband in the Lord – a fond father, a faithful servant of the risen Son of God, who declared the whole counsel of God – a brother beloved, who was constrained to love all who loved the Lord Jesus. Hallowed memories were here, of words faithfully spoken to saints and sinners, of prayers offered in deep affection and fervent desire, of a consistent life maintained by the grace of God. Besides these hallowed memories they had hallowed hopes. Here lay a sower of the seed. For many years the precious seed of God’s truth had been cast by him into the hearts of the sons of men. Fruit had appeared, but the righteous had hope in his death, and the abundant harvest was yet to be seen. How many would be a crown of rejoicing to their brother in the day of the Lord. They had hallowed hopes – they sorrowed not as those without hope. They were anticipating the coming day, the morning without a cloud, when these remains should come up, because of their union with Christ, and spring into beauteous immortality. The spirit that in-dwelt in the body would then be re-united with the body, and they who were the children of God would then with that glorified saint cast their crowns at the Redeemer’s feet, and their immortal lips join with him in ascribing for ever and ever “Salvation to our God who sitteth upon the throne, and unto the Lamb.” He (Mr Victor) would affectionately ask, before they separated, could they who were mourning say, “For me to live is Christ, and to die is gain?” Had they peace through the blood of Christ? Did they know the power of the resurrection in creating them anew, and raising their expectations, and causing them to long for the return of their beloved Lord. If not, might God grant that the prayer just now offered might be answered, that their beloved brother, though dead, might yet speak to them. Mr Victor then offered up prayer, and the mourners having taken a last look upon the coffin – the inscription-plate of which simply bore the name, age, and date of death of the deceased – the vast assemblage left the cemetery. We do not remember a funeral which called forth such unfeigned marks of sorrow and respect.